As I write this, I’m sitting in a bookshop, being a live window display as part of National Bookshop Day. I’m at Eltham Bookshop, one of our many terrific neighbourhood bookstores that do so much to support local writers and readers.

I’m at a little desk set up in the window. Different authors are taking shifts as writer in residence (I took the baton from historian David Day), while people drop in and out, kids try to talk parents into buying the latest book in their favourite series (there is a major Enid Blyton negotiation going on at the counter as I write), and I’m A Believer plays in the background.

I am surrounded by books. Within reach are Penguin Classics from Dickens to Wharton, and the new Text Australian Classics, which include a childhood favourite by Ivan Southall. Bliss. But I have to restrain myself. After four years of PhD focus, my To Be Read fiction pile is currently taller than me.

At present I’m reading Emma Donoghue’s Frog Music. I’m a huge admirer of her nonfiction work in literary history and her previous novel Room, in which the voice of young Jack, who has grown up in one room with his Ma, is a tour de force. Frog Music is a different thing altogether, a return to her previous genre of historical fiction, in this case set in 19th century San Francisco.

It begins with the death of one of the main characters, cross-dressing frog catcher Jenny Bonnet (that’s not a spoiler – it happens on page two). The book then skips from past to present and back again, as Jenny’s friend Blanche tries to understand why Jenny was killed, and by whom, and we experience Blanche’s memories from the moment of their first accidental meeting.

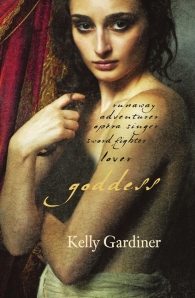

Shifting through time and tense, through characters’ memories, is not an easy juggling act for author or reader as I know only too well. I tried to do something similar in Goddess, in one sense.

Since a few people have asked about the structure of Goddess, and how much I plan in advance when I write, let’s focus on that for a moment.

Goddess has a much more formal structure than any of my previous books, with other organising principles overlaid. It is structured in five acts and a prologue, just like the tragédies en musique in which La Maupin appeared. The scenes in each act alternate between first person monologues (the recitative) and third person ensemble chapters in present tense which give us different characters’ views of Julie and her world.

That’s not quite how the scenes in a tragédie en musique are arranged within the acts, I admit. The acts and scenes at the Paris Opera were shared between the main characters and the ensemble, and passages where the ballet corps took the stage for a divertissement. The recitative was sung using a very refined technique by the lead singers, who also sang airs (arias in the Italian opera tradition), and together in duets or as an ensemble. It was actually Julie’s friend Thévenard who was the master of the recitative, evolving it into a more dramatic form.

But there are some ways in which I tried to replicate the feel of a tragédie – the big show-stopping divertissement is always at the end of the second act, for example. In Goddess, that’s Julie’s debut at the opera. The other less visible structural aspects are the catalogue of sins on which the recitative confession focuses, and the episodic form of the picaresque.

Of course, the overall trajectory is someone’s real story. I tried to track as closely as I could to the reported events in Julie’s life, so I had to know where she was, who was with her (such as the cast that performed in specific shows), seasons of the year, other things going on in France at the time, what people were reading, singing, wearing.

Did I plan it? You bet. You should see my spreadsheet. It’s a monster. It had to be.

A couple of people have asked about the idea of the book starting as a death bed confession – just as in Frog Music, you know the “end” of the story from page one.

I haven’t done that before, and it was one of the first creative decisions I made when writing Goddess. It’s a big call, I know (setting aside the fact that a quick squiz online or in an encyclopaedia will reveal Julie’s life – and death – story). Is it the end, though? Is it the point of the story? Or is that in the telling? Or both?

Then there’s the memory – Julie’s memories, and other people’s. Many of the third person scenes have a shifting point of view, an internal structure that (I hope) plays with perception and explores the idea of the spectator. How did all those people see Julie? What did they make of this remarkable creature in their midst, striding around in her breeches and cloak? How do different people perceive and remember the same incident? How does she remember? Why was she such a celebrity and what did celebrity do to her – and her legacy? How do the memory and the monologue connect?

I hesitate to use the term “flashback”. It has become such a cliché. But I’ve just been binge-watching the Netflix series Orange Is The New Black, in which creator Jenji Kohan uses flashbacks in such an interesting way. We meet its huge cast of characters as women in prison, get to know them a little, and then one by one across different episodes their past lives are revealed, in some cases dramatically different to the persona we’ve got used to. Makes sense. They are different people in prison. The flashbacks may explain their crime, but may not – they reveal something about the choices each woman has made, the people they were, the turning points that somehow got them where they are now. What’s even more fascinating is that the actors involved have to create these characters from the beginning without knowing that back-story – in most cases they don’t even know why their character is in prison. They may never know.

In Frog Music, on the other hand, we start off knowing the crime but not the people. We as readers will make our way together, with Blanche, through the aftermath and her memories of the time leading up to the murder. I know that a crime has been committed, but I have no idea what will happen next.

There’s a great moment in Orange Is the New Black when the main character Piper returns to the main prison camp and has to retrieve all her belongings – the other inmates assumed she was long gone. She grabs her copy of Ian McEwan’s Atonement out of someone’s hands, shouting “Everyone dies!”

The ultimate spoiler, for one of the most excruciating shifting memory structures in recent fiction. I remember reading the final passages of Atonement for the first time and shouting in fury, while at the same time I couldn’t help but admire it.

Now THAT’S a flashback.