No. Not that Voice.

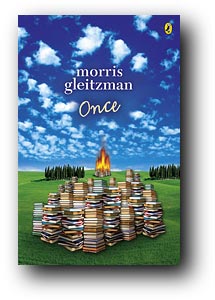

I’m reading Morris Gleitzman’s Once, told in the voice of a small Jewish boy, Felix, wandering wartime Poland in search of his parents. He’s unaware of the scale and meaning of the Holocaust happening around him, and misreading all the signs – not just because he’s young but also because he is fundamentally good. Foreboding drips onto every page. It’s both gorgeous and dreadful to read.

Felix’s voice is very direct, speaking straight to young readers (and people of any age) so that you immediately attach yourself to Felix and see the world through his eyes, even though you – knowing what you know – also can’t, at the same time. Gleitzman has said that the series was triggered by the story of the life (and death) of his hero, the Polish doctor and author Janusz Korczak, and extensive research into contemporary accounts of and by child victims and survivors of the Holocaust. Once must work quite differently for young readers who don’t have information about what is happening in Felix’s world, but those who do know are still somehow conveyed into the world view of that small Polish boy – even though for us, being without knowledge of the Holocaust is realistically impossible to comprehend now that we do have that knowledge, now that the world has been changed by it.

As a writing feat, that’s tricky to pull off. (Another sublime example is Jack in Emma Donoghue’s Room which, although not historical, requires the same balance of belief and disbelief at once. ) But it’s not just that which interests me. The ahistorical voice works particularly well for young readers. You’d think it’d be easy, but it isn’t. It’s not the same thing as writing in a modern voice, but is something else – based on a modern voice but with no (or few) jarring historical anachronisms. The modern voice – the author’s own transitory dialect – will date. The ahistorical voice will last a little longer.

The writing process requires deep research not just into historical events and details but also into contemporary speech patterns, vocabulary and world view so that they can be present without being visible. Hilary Mantell has explained how she does it: ‘I use modern English but shift it sideways a little, so that there are some unusual words, some Tudor rhythms, a suggestion of otherness… If the words of real people have come down to us, I try to work them in among my inventions so that you can’t see where they join.’ (1).

I reckon it was first mastered, especially for young readers, by people like Geoffrey Trease in those golden post-war decades, creating fiction that was different to what Trease called “costume drama”: that is, where there is a great deal of historical accuracy about details of food and dress and perhaps even words, but no contemporary empathy – no understanding of the essential world view of the characters. It’s one reason Wolf Hall is so fine, and some other Tudor novels filled with “prithee” and “pray you” not.

This is partly what I’m working on now, although I have a long way to go before my fiction lives up to my theory.

I’m on the side of V.A. Kolve who suggests: ‘We have little choice but to acknowledge our modernity, admit our interest in the past is always (and by no means illegitimately) born of present concern.’ (2)

And get on with it.

Can’t say anymore. Have to go find out what happens to young Felix.

(1) Mantel, Hillary, 'The Elusive Art of Making the Dead Speak', Wall Street Journal, April 27, 2012 (2) Kolve, VA (1998)'Ganymede/Son of Getron: Medieval monasticism and the drama of same-sex desire', Speculum, 73 (4), 1014-67.