Was it only last week I spent days live-tweeting the 2013 Reading Matters conference? I didn’t have time or head space to add any thoughts of my own at the time, so here are a few now.

A great line-up of authors debated a wide range of issues but there were a couple of thorny topics that just wouldn’t go away – as usual, chief among them was gender.

A few questions almost always come up in conferences, seminars and conversations, especially with school or children’s librarians and teachers, such as:

- How do we get boys to read?

- Why don’t boys read books with female protagonists?

- Why do the book covers aim at readers of particular genders?

I can’t pretend to be able to answer those questions, but I do want to reflect on how and why the questions and answers are framed.

Many times I’ve listened to an author try to answer the question ‘How do we get boys to read?’ I get asked it myself, all the time. I sympathise, I really, do, because I understand that it can be very frustrating for professionals and parents. But…

1. You are asking the wrong person. Just about every author ever asked that question answers something along the lines of: I just write the stories I need to tell. Some are aimed at boys, some are aimed at girls, some are neutral.

2. Some of the gendering is about the package – the cover, the blurb, the author’s gender or name, the marketing, the industry, socialised reader expectations, the context of both reader and book. Sometimes that’s perfectly appropriate. Often it’s not. Take a look at some examples in Maureen Johnson’s Coverflip experiment if you doubt it.

From the Coverflip experiment

3. Boys do read. They read all sorts of stuff. Even those who read according to strict gender stereotypes immerse themselves in narrative through games and movies; they may love non-fiction; they read basketball magazines or music blogs or comics; they read facebook and use the web and their phones; and they do endless amounts of homework. They might not read my books or other books with girls on the cover – which is a different question – but that’s not the same as not reading at all. Not everyone has to read the same thing.

4. There are actually many authors who do consciously write for boys. Without even reaching for names I can think of Keith Gray, Jack Heath, Brian Falkner, Richard Newsome – not to mention the bulk of the Western canon.

So here is the most important thing: The entire world is constructed for boys. Can we stop pretending they are some oppressed minority, stop asking us to arrange the stories we write and publish to their (perceived) narrow interests?

Suck it up, guys. As Gayle Forman asked at Reading Matters: “Why is it acceptable for a girl to enter a male world but not the opposite?”

Why do we accept that world-view so carefully constructed for them by society?

Why is it too much to ask a boy or young man to see through other eyes? Does it mean you can’t ask them to see through anyone else’s eyes – to read about anything outside their own experience? And if so, what does that say about how we are framing the future?

Are you telling me that a fourteen year-old boy can relate readily to a hobbit or an assassin or a forty year-old man, but not a girl?

I don’t believe that.

At Reading Matters, Libba Bray said: “There are not boy books or girl books. There are just books.”

I think that’s true, to an extent, although there are some stories and some authors who do aim their books at one gender or the other, just as we aim our books at certain age groups, quite consciously, depending on the story. Keith Gray writes for boys, hoping, he said at the conference, not to alienate female readers.

As Miffy Farquharson tweeted during the conference: “Teacher-librarians are good at ‘guessing’ what young people would like to read. Often it’s just ‘a good book’.”

Readers are always asked to make imaginative leaps – into fantasy worlds, or along ziplines between buildings, or into the past. We might be asked to read the story of someone we despise or can’t trust. Female readers constantly take the imaginative leap into the minds of male characters. Kids who are queer may spend their entire lives seeing the world through the eyes of straight characters. Happily, there is now a greater diversity in stories and characters than ever before, so that young readers from different cultural backgrounds or life experiences can find some stories that reflect their world. But much of the time, they’ll be reading about someone completely Other, and they relate – they find some imaginative or emotional connection with those characters, they see something in those lives that makes sense for them, they read to witness another world, another way of seeing. Vikki Wakefield noted in one panel: “Age and gender do not define a reader.”

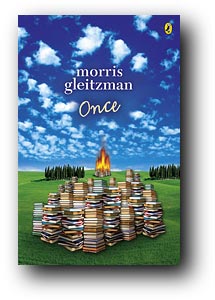

The world is filled with different perspectives and readers get to experience those perspectives, to see the world through different eyes – to see new worlds, feel unfamiliar sensations and emotions. If boys don’t get to do that, never make those leaps, they’re missing out dreadfully. They can do it – of course they can. They do it all the time – even the most stereotypical readers or gamers or movie-goers imagine themselves into pirate ships or D-Day or Westeros. “If we do our job properly,” said Morris Gleitzman on one panel, “boys will read girl characters.”

Calling for narratives that support that limited world view only perpetuates the problem – for the boys, and for the rest of the world. It continues to limit them, reduces their world view and doesn’t even echo back to them the world in which they live. Nor does it recognise the diverse lives and experiences of young males in our world, as if they are never outsiders, as if they are never readers, as if they don’t share the same fears and hopes and emotions as everyone else. It defines them as people who will only read The Guinness Book of Records or short action-driven stories (not that there’s anything wrong with either). But as Gleitzman noted: ‘There’s not a boy on this planet that doesn’t understand love gone wrong”.

And…

Why do we always end up here? What about discussing the girls who are struggling? The boys who love to read? The girls who consume books? The girls who love to read adventures and war stories and fight scenes? The readers who read regardless of gendered covers or narratives or protagonists?

Why do we always end up here in spite of the fact that every available piece of research tells us that books featuring female protagonists and/or by women authors are less likely to be in the big prize shortlists; that they are less likely to be reviewed; that women are less likely to be writing the reviews; that in spite of the huge proportion of women authors, publishers, teachers and librarians, the people most often in the positions of decision-making power are men – totally out of proportion to the number of men in the industry (as is the case with most other industries where women are in the majority, such as teaching)?

Why, in spite of all that research, would someone perfectly sensible like Keith Gray suggest at Reading Matters that books for or about boys suffer discrimination due to the “female domination” of the book industry – and why would a whole lot of women in the audience agree? What is that about?

Final word to the brilliant Gayle Forman: “If Harry Potter had been about Hermione, it probably wouldn’t have been such a success.”

Case rests. For now.

Note: These are my views as a writer and reader, not in my capacity as a Library person.