People – especially emerging writers – often ask me what happens when you publish a book? How long does it take? Can you say you don’t want to change anything? Do you get any input on how it looks? Don’t you resent being edited? (Short answer: no, I love it.)

Well, here’s what usually happens in traditional publishing (and is happening right now, for Miss Caroline Bingley, Private Detective):

First, you write your book. I know that sounds silly, but plenty of aspiring writers worry way too much about getting published before they’ve actually finished the thing. I get that. It’s scary and also exhilarating to think you might one day publish a book, but you won’t publish anything at all if you don’t write it first, and make it as good as it can be.

Second, you pitch your book. That’s a whole topic of its own so I won’t bang on about it, and anyway I leave that to the experts nowadays – my fabulous agents at Jacinta Di Mase. They know what they’re doing, and they do all the hard work.

Then, once you have secured a publishing contract, your publisher’s processes kick in.

Editing rounds

So, you get early feedback on the manuscript from the publisher. These might be queries about plot points that miss the mark somehow, or about character development or voice: the big questions that an expert eye picks up, from someone who really cares about the book. Your publisher also knows what else they’ve got coming out (maybe similar titles, or in the same genre), in general what other houses have out, what the market’s doing, and what readers expect.

You have a think about any issues they’ve raised, respond accordingly with any amendments, and submit your final manuscript. Your book is given a slot in the publishing timeline which gives everyone enough time to work on it, but also aligns it with overall strategy (eg, not clashing with another similar title, lining it up for Mother’s Day or Christmas sales, hitting shops at the right time for its anticipated readers). At this point, your agent or publisher will start pitching it elsewhere – for translation rights, or adaptation.

Then there’s a structural edit. This may be done by an in-house editor or outsourced – either way, it will be done by someone who knows their stuff. They focus on big structural issues like character and plot, and their fresh eyes can pick up continuity errors or variations in voice, for example. They might recommend structure or plot changes, or point out the need for more clarity. Often they ask questions rather than edit – they leave the resolution up to the author. I’ve never had a serious argument about anything significant with an editor or publisher, and find that questions are usually insightful and all about making the book better.

Ideally this feedback also includes any outstanding issues from the publisher. In the case of Miss Bingley, our publisher, HarperCollins, brought together any feedback from all three publishers who are releasing the book (Australia/NZ, UK and US), plus the editor’s notes. And as the book is co-written with Sharmini Kumar, the two of us had to go away and figure out what we thought about anything significant, and we both went over the manuscript again to make any changes.

By this time, generally, you’re pretty sick of reading your novel, but again, you read through it all, correct any errors and give thanks they were discovered early on (!), and again amend the manuscript to make sure it works for you and the publisher.

But there’s no rest for the wicked, since after that comes the copy edit. Again, this is done by a professional editor, in-house or outsourced, who goes over the manuscript word by word, line by line, noting any errors (simple things like missing words or typos) and making suggestions about anything they find – might be word choice, sentence structure, the rhythm of a scene, overall pacing, dialogue, plot – anything. And when it’s historical fiction, they also ask questions like, “are you sure that type of hat was worn that year?”, to send you scurrying for your research notes (they are usually right to ask). And again you go through it, word by word, line by line, accepting their suggested changes, coming up with your own solutions, or flagging things for further discussion.

The look of the thing

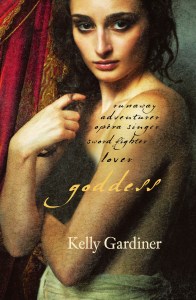

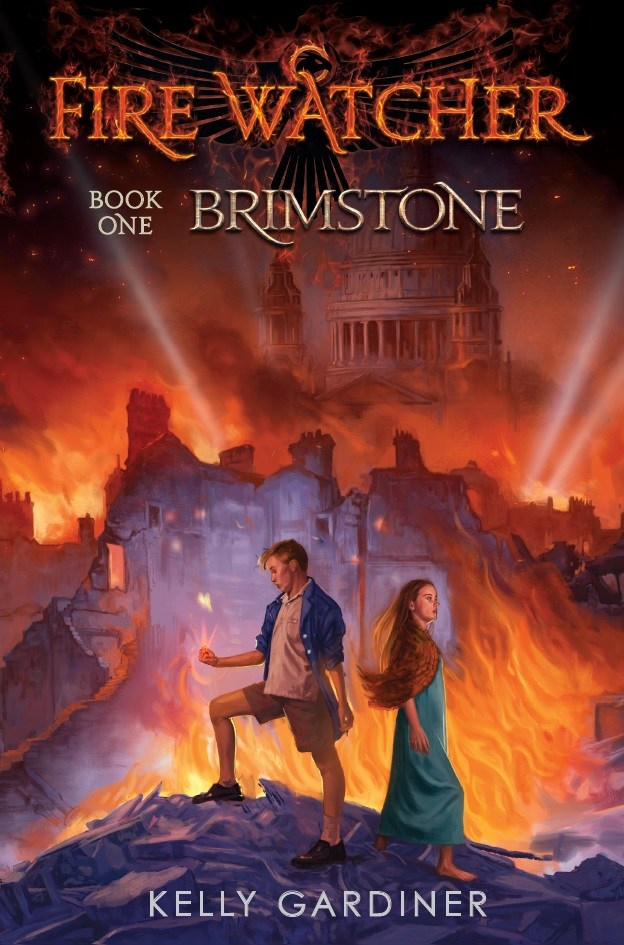

By now you probably have some cover concepts presented to you. It happens sometimes that authors hate their book covers, but I think it’s pretty rare, since publishers want you to love it. After all, you have to sell it too. Sometimes you get a few options to choose from, and sometimes they design different covers for different publishing territories. Whatever happens, I always go into the process knowing (from years working with designers in print media) that it’s someone else’s creative process, and I respect that. By the time it gets to you, a lot of people have worked on it, and they know what they’re doing, but you usually get a chance to make suggestions as well. (A confession: I asked for more arm muscles on the Julie figure on Goddess! Got knocked back on that. But that was such a gobsmackingly gorgeous image, and cover, I was very happy. And anyway, it wasn’t her sword arm.)

After the copy edit, your changes are incorporated, there may be a bit of back and forth about little things, and then the book is typeset. Yes, we still call it that. Every book has an internal design, even if you don’t really notice it, with creative decisions on typeface, chapter headings, drop caps, etc. This is the critical stage, because after this, it’s hard to change anything major.

Once it’s typeset, everyone proofreads it, over and over, even though by now you never want to see the bloody thing again. For some books, there’ll be a slightly different edition for different territories – the main issue is US spelling for that edition.

For each of these stages, you’re on a deadline and so are all the people behind the scenes at the publishing house. So be kind to anybody who says they’re proofreading or working through copy edits. They may have letters dancing before their weary eyes.

While this is happening, advance reading copies (called ARCs – without your final corrections) go out to booksellers, reviewers and journalists. So this is the first time your book is out in the world, even though it’s semi-secret and may contain errors. These early copies are for people who need to know in advance what the story is, who it’s for, and what they can do with it – order a million copies, set up interviews, book you for festivals, or get ready to review when it hits the shops.

And from then on, it’s in the hands of the publisher’s sales, marketing and publicity teams for pre-order, then promotions and sales to booksellers. And eventually in the loving hands of your readers.

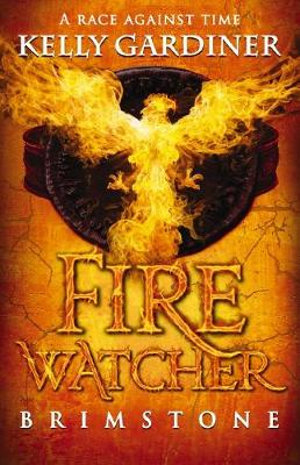

All of that, in the case of Miss Caroline Bingley, Private Detective, will have taken about a year and a half, from contract to publication in April 2025.

We can’t wait to get her into your hands.