I recently chaired a debate between historical novelists and historians at the conference of the Historical Novel Society of Australasia: ‘What can historical novelists and historians learn from each other?

Our thoughtful and entertaining panellists were Jesse Blackadder, Gillian Polack, Rachel Le Rossignol, and Deborah Challinor.

It was great fun, but of course being in the chair meant I couldn’t answer any of my own questions.

But it’s my blog and I’ll rant if I want to.

So here begins a series of posts on thoughts about the intersections of history writing and historical fiction: arising in part from the conference debate, tracing the questions I posed (and also many that I didn’t get to ask), but also bubbling up from my own reading. And some tips for writers of historical fiction on how to act on some of the issues raised.

The HNSA conference in action: Balmain Town Hall. (Photo via HNSA facebook group)

So… this is where we began the other night:

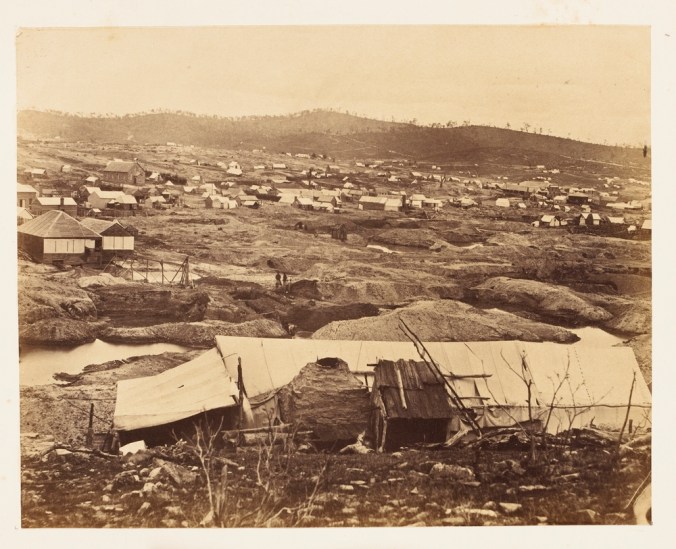

Without history writing, without libraries and other collections, archaeologists, without the ancient recorders of events and daily life, what we novelists write would be fantasy. On the other hand, we know that fiction works as a gateway drug to history writing and research for both readers and writers. But how alike are these two forms – these two disciplines?

And what techniques, skills, tools and models might they share?

Of course the work of history is diverse, and practice and approaches change dramatically over time. But if historical imagination operates in both history writing and historical fiction, does it work differently – does it feel different to the writer as well as the reader? Does narration work differently? Does interpretation?

Does the history we present look different?

Those are some of the questions I’ll cover in the next few posts.

A proposition

If history writing and historical fiction are about “understanding what it means to be human” (Carl Degler, 1980), are they part of the same project? Practitioners of both forms seek out stories from the past, engage with them creatively, sort and interrogate them, pull them into some kind of narrative shape and interpret them for readers.

That seems so obvious, but the ongoing conversation between historians and historical novelists has been rather testy at times. There is misunderstanding on both sides (if indeed they are ‘sides’) about the commonalities, purposes and practice of both disciplines.

You will often see, for example, historians portrayed in fiction as rigid, data-obsessed researchers (the same might be said of many fictional portrayals of librarians – and academics). They are gatekeepers guarding facts, keeping novelists and readers in the dark about what really happened.

And yet writers of historical fiction depend on writers of history texts – creators of secondary sources – for the information they use to build their imagined worlds; worlds that are, according to Jerome de Groot, “manifestly false but historically detailed.”

What’s going on here? Let’s try to clear the air.

It ought to be clear to us all that the writing of history is a creative process, just like the writing of fiction. It has been since the days of Herodotus. Equally, we can all recognise the depth of research that goes into many works of fiction. So we have a great deal in common. But our approaches may be different – of which more in a later post.

There is, as Gillian Polack pointed out during the debate and in her own writing, an idea of history and historians based on nineteenth century concepts of not just the historian figure but also what the field of history is, does and means. The discipline – the work of interrogating and engaging with the meaning of history, even our understanding of what that word means – changed radically during the twentieth century, and continues to change. But many people haven’t noticed.

I agree with Gillian that historical novelists tend to see ‘history’ in its nineteenth century guise – that thing we all fell in love with in school or in early historical novels – and our responses to the corpus of history writing are seen through this lens. That means we also run the risk of seeing even primary sources and the research process itself from this limited viewpoint. Without an understanding of historiography, of approaches to the work of history, we run the risk of relying on outdated concepts and disproved theories.

Here’s a simple but striking example, discussed by Gillian in one of her articles: Historicising the Historical Novel: How Fiction Writers Talk About The Middle Ages. As a medievalist as well as a writer of fiction, she can see how many novelists view the Middle Ages through the lens of nineteenth century British and French medievalism – that gorgeous romanticised William Morris tapestry version that projected Victorian values onto a certain version of ‘the past’, and influenced many generations of historical novelists. It is, as Deborah Challinor memorably pointed out in the debate, the past without the pus – without a realistic view of life for real people.

Regular readers of this blog will know that I often sound off about the myth of authenticity: this idea that fiction can somehow capture the actual experience and voice of people in the past. It’s nonsense. Or rather, it’s not authenticity, but an expected form of the genre, perfected by Walter Scott and others.

What writers create and readers have come to expect is the medievalist view of the world (even of eras that are not medieval) – it has nothing to do with authenticity, and may indeed have little to do with actual history.

If that’s what you’re writing, all well and good. Recognise it for what it is – medievalist fiction. That’s a thing. But it doesn’t need to run the risk of being incorrect or based on out-of-date data.

What next?

So what can we learn and do?

Keep up to date with new thinking and writing about the theory of history. I find it fascinating: you might not.

At the very least, read current research about the era on which you write, explore new data and interpretations. (I’ll post later about research methods and historical thinking.)

Write with clear(er) eyes about our subjects. We can enrich our world-building and characterisation with recent findings, and our own work with primary sources will be enlivened and informed by the latest analysis by experts in the field – and in other fields. I follow archaeologists and anthropologists as well as historians, for example, and read updates and debates everywhere I can, from Twitter to specialist history societies, from academic or professional journals (available free and online through your nearest state or national library) to popular media such as the BBC’s History magazine or Inside History.

History and fiction are a tag team, sometimes taking turns, sometimes working in tandem, to deepen our understanding and imagination – Tom Griffiths, ‘History and the Creative Imagination’, History Australia, 6: 3, 2009.

Some reading suggestions

If you really want to get your teeth into some of these issues, try these:

Is History Fiction? Ann Curthoys and John Docker, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2006.

Re-thinking History, Keith Jenkins, Routledge Classics, London, 2003 (first published 1991)

The Historical Novel, Jerome de Groot, Routledge, London, 2009

The Fiction of Narrative (Essays), Hayden White, John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2010.

You might be able to access the journal Rethinking History through your library.

And here’s a list of Gillian Polack’s publications.

To be continued…