People often tell me that they don’t read historical fiction. Ask them if they’ve read Possession or Oscar and Lucinda, though, and they’ll say, “Oh yes, but that’s different.”

Are they right? And if so, how?

I recently attended the London conference of the Historical Novel Society where, it must be said, almost all the authors who spoke identified themselves as writers of the genre.

But not all. Emma Darwin and Suzannah Dunn both said they didn’t define themselves as historical novelists, and Lindsey Davis, creator of the Roman detective Falco, said: “I don’t write historical fiction. I write literary fiction.”

How interesting.

I’m trying to get my head around something here, so bear with me. Please.

Historical fiction is (arguably) a genre, and as such it has common tropes, familiar forms and styles; guidelines, perhaps, rather than rules. It’s a broad church, of course, and encompasses many eras as well as approaches to technique such as point of view. It contains many sub-genres and genre overlaps, too, such as historical romance, crime, thrillers, and fantasy, and has some particular obsessions (Romans, Vikings, Tudors … and Jane Austen). It can also include time travel or alternative history, and those many stories that move back and forth between eras. Some of it is classed as commercial fiction, while some is categorised as literary fiction. One of its less discussed features, on which I’ll write more soon, is that it is quite often overtly gendered – warriors for blokes, remarkable noblewomen battling the odds for female readers.

The Historical Novel Society defines it broadly as:

To be deemed historical (in our sense), a novel must have been written at least fifty years after the events described, or have been written by someone who was not alive at the time of those events (who therefore approaches them only by research).

Does it have a recognisable form? Its origins are debated, but in The Historical Novel, György Lukács (1962) identified Sir Walter Scott as the originator of the historical novel. It’s absolutely true that other people, including women such as Madame de Lafayette, wrote novels set in the past much earlier than Scott’s 1814 blockbuster Waverley. But I think it’s fair to say that, for better or worse, Scott was instrumental in setting down (at least for readers of English) expectations of what a historical novel might be, how it might sound, what it might include – setting, plotting, character; even that it might fool around a bit with historical accuracy. It created, above all, an expectation of voice, a concept of ‘authenticity’ that is, perversely, completely false and based largely on Scott’s own style. Lukács called it ‘historical realism’, and it’s that form that you read in Tolstoy, say, and the early historical novelists.

It has evolved into new and various forms. But when normal people – readers – talk about historical fiction, often what they mean is a costume drama with epic twists and Gothic plotlines, set against a rich and detailed backdrop. Think of those addictive Georgette Heyer or Jean Plaidy books and later Bernard Cornwell or Diana Gabaldon. It is often seen and marketed as commercial fiction, too – like Heyer’s.

(One hopes for accuracy in characters’ contemporary world views, too, and these can be found in many of the best historical novels. But it’s not, apparently, required. There are a great many New Age Georgian guys and feminist princesses reflecting modern ideas and not their own. I’ll come back to this.)

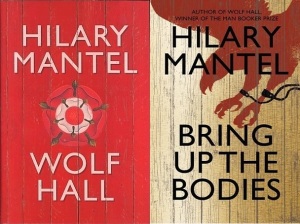

Hilary Mantel’s Thomas Cromwell novels, I think, are something else entirely, something closer to War and Peace. They are works of literary fiction which are immensely popular, perhaps because of the obsession with the Tudors generally and Anne Boleyn in particular, and also because they happen to be brilliant. Compare them to the Tudor books of Philippa Gregory, for example, which are more obviously written in the traditional historical fiction mode, and it’s clear that they are a different form. Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies are works of twenty-first century realist fiction set in the past.

Let me be clear. I’m not making any value judgements or setting one form above the other/s. I am a proud reader and writer of genre fiction. I’m not interested in creating a binary of a canon versus commercial genre. I’m just trying to understand and refine our definitions, and perhaps our expectations.

People shy away from the label ‘literary fiction’, partly because it’s not easily defined and also, particularly in Australia, because it has been branded as elitist and inaccessible (though it isn’t, at least not essentially). Perceptions of it are bound up with certain 20th century styles of writing which began as modernist innovation and became canon – literary fiction isn’t limited to any one form or style, but sometimes perceptions of it are.

Which is a pity. We really ought to get around to reclaiming it one of these days.

Literary fiction is definitely not a genre – it is an even broader church, but let’s agree that it is often concerned with form and experimentation with form, with ideas – including ideas about fiction and writing and narrative. It’s an invitation to explore language and meaning, the way we use words and construct ideas with them; to question and satirise and experiment.

So. Can we agree that literary fiction which happens to be set in the past is different in intent to historical fiction that fits easily into the expectations of the genre? When Peter Carey or Margaret Atwood set a story in the historical past, they are not called ‘historical novelists’. But Alias Grace and True History of the Kelly Gang are among the finest novels of recent years that are set in the past.

And then there is fiction that operates at the intersection of these two forms: the most obvious example is The Name of the Rose, which is one of the best-selling historical novels of the modern era, but operates on many different levels, including a complex metafictional and semiotic framework based on Eco’s years of study in the area. Think too of AS Byatt’s Possession. The Luminaries. The Passion. The Secret River. Atonement. The English Patient. Ragtime. Beloved. Love in the Time of Cholera.

I can see a Venn diagram in my mind. It’s too hard to draw, but in the overlap of the historical and literary circles are also titles which veer more towards the traditional. The recent success of Hannah Kent’s Burial Rites is a good example: literary in style, but happily recognisable to fans of the genre. Year of Wonders. Birdsong. Angels and Insects. The Song of Achilles. The Regeneration trilogy.

Sarah Waters’ entire publishing history works at this intersection, as does Nicola Griffiths’ Hild – transgressing not just genre but also publishing expectations about what’s permissible and popular in writing about gender and sexuality.

And there’s the rub.

Sometimes it works.

Sometimes it works against the success of a book.

People who love reading ‘traditional’ historical fiction may dislike literary novels set in the past if they don’t meet their expectations of the genre or sub-genre. Or vice versa.

On the other hand, readers, reviewers and book page editors may not pick up a title classified as historical fiction, but would if it was seen as literary. A panel at the HNS conference suggested historical fiction suffers from a certain snobbery, and especially if it’s historical fantasy.

‘Historical novels have often been sidelined or derided for not being serious enough, or taking liberties with facts,’ writes academic Jerome de Groot, ‘[…] as a mode that encourages a sense of the past as frippery and merely full of romance and intrigue.’

A recent feature on Sarah Waters’ new novel The Paying Guests, noted:

Don’t let the words “historical fiction” dissuade you. Waters’ writing transcends genre: her plots are sinuous and suspenseful; her language is saucy, sexy and direct; all of her characters, especially her lesbian protagonists, are complex and superbly drawn.

It seems ‘historical fiction’ is something that might turn off some readers, as if it doesn’t contain suspenseful plots, terrific language and characters. As if it’s just not good enough, or not everyone’s cup of tea. As if to be classified as such will alienate potential readers. (Of course, the same might be said of literary fiction.) As if millions and millions of people don’t read it and love it.

What are they getting at here? Waters’ great strength is her ventriloquism. She manages to capture, in voice, style and in character world view, the literature and the detail of the era in which her books are set. She manages to put it into words that sound both of the era in which the book is set and of our own time; thoughts and preoccupations that feel real and contemporary to us, even though they are not of our time – the spiritualism in Affinity, for example, or the bleak post-war desolation of The Night Watch. It never feels like costume drama (except in Tipping the Velvet).

You see? These definitions matter – to readers and to reviewers and commentators, if not to the writers.

The ventriloquism we hear in Byatt or Waters is not the only alternative approach to Scott’s version of historical voice – I’ve written about this before, so I won’t bang on.

It’s different to the voices and characterisations you’ll find in more traditional historical fiction and, importantly, Waters is willing to focus on characters who are complex, perhaps annoying and unreliable, not necessarily heroic, sometimes downright unlikeable (Maud, in Fingersmith – and yet somehow we fall in love with her … or was that just me?).

So perhaps it’s not that Waters “transcends genre”, nor that there’s anything wrong with the genre – it’s just that her work’s not the same kind of project as some other novels you might read that more clearly fit into the genre of historical fiction.

The same can be said of Mantel, of Catton, of Grenville, of Eco. Perhaps they are simply not trying to do the same thing as Cornwell or Gregory?

Perhaps it’s a spectrum, rather than a Venn diagram.

So what does that mean?

I don’t know that it’s realistic to broaden popular ideas of what historical fiction is. Let it be.

Perhaps instead we can try to define a new form (not a genre) that includes what Linda Hutcheon called ‘historiographic metafiction’ and/or embraces experiments with voice and style, with structure and form, even with history and the way people move through time.

We have enough examples of it from the last few decades. I can see it clearly enough to consciously write Goddess in that framework, although it has few rules and very soft edges.

It doesn’t need to be defined or have boundaries placed around it – in fact that would defeat the purpose. But it could include writing that:

- May run contrary to expectations of ‘historical authenticity’ in voice

- Is willing to experiment with form, language, point of view, and structure

- Consciously operates on the edges of historicity

- Interrogates concepts of time, memory, story-telling, and history-making

- May subvert the rules of historical fiction and/or any other genre

- May be interested in questions of gender or subvert expectations of gender.

It might be realist or fantastical, test the boundaries of point of view (just how close can Mantel take third person?) and play with notions of historical voice (Winterson’s postmodern Sappho), layer structure and framework and metaphor and time. In fact, I wonder if perhaps subversion is one of its key features?

What else?

And what to call the literary form, if indeed it is a thing? The word ‘literary’ isn’t useful, loaded as it is. But what might it be?

Are the two forms genuinely distinct, or are they two sides of the same coin? Or is it dangerous, or unnecessary, to separate the two?

I dunno. Do you?

Contemporary history can be rendered into engaging narratives. One does not have to write about the distant part to earn the label of historical novelist.

That’s true – I think, technically, the definition of historical fiction is writing set fifty years ago, or before the recollection of the author. But I know some of my students consider fiction set in the 80s or 90s to be historical, whereas I think that’s only yesterday! I guess the main question is whether or not you need to do research into the past – however distant – in order to create your story.

Cheers,

Kelly